|

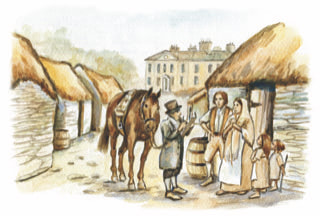

The above illustration entitled 'Small Notebooks - Big Egos' is an illustration by the talented Gerardine Cooper Sheridan. It is from an upcoming history of the Coollattin Estate by Kevin Lee. © Coollattin Canadian Connection

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ It is clear from the records that information relating to families who wished to apply for assistance to emigrate was collected in small notebooks by the many estate sub officers such as wood rangers, gamekeepers, drivers and assistant drivers who daily traversed the highways and byways of the sprawling south Wicklow estate. These employees would also garner information on the families who, due to rental arrears or some other reason, were being prioritised for placement on the proposed emigrant lists. Much of the documentation arriving at the Coollattin office was kept in an undiluted and raw state. For subsequent researchers this has its advantages. The homespun information regarding tenancies, problems encountered by those living on the estate, recommendations relating to assisted emigration and complaints relating to those who were in breach of estate rules and regulations was being recorded and transmitted to the office at Coollattin . The records kept by these sub agents contain phonetic spelling, poor grammar and in many instances extraneous information bordering on idle gossip. Returns made were used to compile well structured manuscript books. The field books from the early 1840’s provide us with an insight the criteria used for the selection of assisted emigrants. It is abundantly clear from the notebooks that emigration was the desired option for many tenants who were walking the thin line which divided existence from subsistence. Of prime importance seems to have been the age of the house and the number of years that the family was living in it. Matt McDaniel who gave his occupation as a blacksmith had lived in the same house for ten or twelve years. Of Matt it was stated that he was ‘anxious to get his name down in the office.’ Thomas Neal who lived in the same townland had lived in his house for 24 years. Their neighbour John Lambert was living with his wife and eight children in a house which his family had occupied for ‘near fifty years’. It is quite a surprise that in many instances information given by the occupant’s wife was recorded in the survey being undertaken. In John Sumers’ case it was stated that ‘the wife says that the landlord will alow(sic) the house to be taken down’. Sumers held nine acres from a ‘Mr McKenna a son in law of Mrs Edge’ He had six children aged between24 and 2. Thomas Hutton of Sleaghroe had lived in his house for eighteen years. The Huttons had eight children as well as John Boyde ‘a boy they had reared’ John was aged 21 and was a year older than the eldest in the Hutton family. The person conducting the survey intimated that the information had been provided by Hutton’s wife Charlotte who also said that the landlord will allow the house to be taken down’. In the case of Thomas Keegan it was the housekeeper Dolly Goss who provided the information that the Keegan family had occupied the house for forty years and that if granted assistance the house would be taken down. Information regarding these neighbouring families was collected during 1846 and they were amongst the first emigrants who travelled to New Ross to board a Graves owned vessel bound for Quebec. If a family was to succeed in obtaining assistance to emigrate it was imperative that a undertaken to demolish the family home or cabin should be given. Edward Murphy of Molanaskay sought to get a head start on his neighbours when he demolished his house and took lodgings in the village of Tinahely. In one entry a request is made ‘to let Thomas Neil’s house stand as it will make an out house for Pat Doyle’. The powers that be at Coollattin were not prepared to risk of another family taking up residence in the old house and the word ‘Deny’ was boldly written after the request. There is a certain irony in the entry for Pat Gahan of Killinure. Pat it was stated ‘has no house to come down therefore will not be sent’. One would have thought that if he was homeless he would have had a stronger case for the granting of assistance. Every care was taken that the materials from houses ‘thrown down’ would not be recycled and used to erect new domiciles. In June 1842 Richard Barker, an estate driver, was instructed to go to Racott on Thursday week to see James Kenny and Doyle and Bryan cabins pulled down. James Kenny to have one pound, Doyle ten shillings and Bryan the timber and the thatch’. The estate employees who traversed the sprawling south Wicklow estate recorded, side by side with the cases being made for assisted emigration, cases requiring litigation by the estate on matters of dispute both within individual families and between neighbours on the estate. Many of these cases referred to reflected the Fitzwilliam paternalistic role in dealing with his tenants. In November 1841, ‘Cundell of Sleaghroe’ was summoned to attend the office in Coollattin to answer questions relating to ‘turning out his father’. Pat Neill was summoned in ‘about his son and daughter’. In a similar vein Charles Tumpkin was asked to appear in relation to ‘the distress of his sister’. One can only speculate on the popularity, or otherwise, of the official who managed to locate seven tenants who had in their possession ‘thorns supposed to be cut on John Jones land’. Five tenants, Dan Dagg, William Driver, Pat Dolan, Miles Travers and Miles Dillon were given the seemingly impossible task of replacing in situ sods of turf which they had cut and removed. All of the tenants residing in Toberlonagh were asked to appear at Coollattin to answer questions relating to ‘the stopping of John Byrne’s water’. There could be no mistake in the identification of the man who had in his possession ‘lawn grass’ from Coolboy Hill. He was described as ‘Matt Breen who had married the widow Fox and lives in Drumingle’.

7 Comments

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed